Federalist No. 10 stands as a seminal document in American political theory, authored by James Madison under the pseudonym Publius.

It tackles the issue of factions—groups of individuals united by shared interests that are contrary to the rights of others or the interests of the whole community.

Madison’s paper is a pivotal argument in favor of the Constitution’s formation, specifically its potential to control the damaging effects of factions and preserve the public good.

Key Takeaways

- Liberty is essential. It’s the foundation of political life in a free society.

- Factions are inevitable. As long as people have different beliefs and interests, factions will form.

- The solution is not suppression. Factions can’t be eliminated without sacrificing freedom.

- A large republic is the remedy. It dilutes factions and makes it harder for any one faction to dominate.

Historical Context

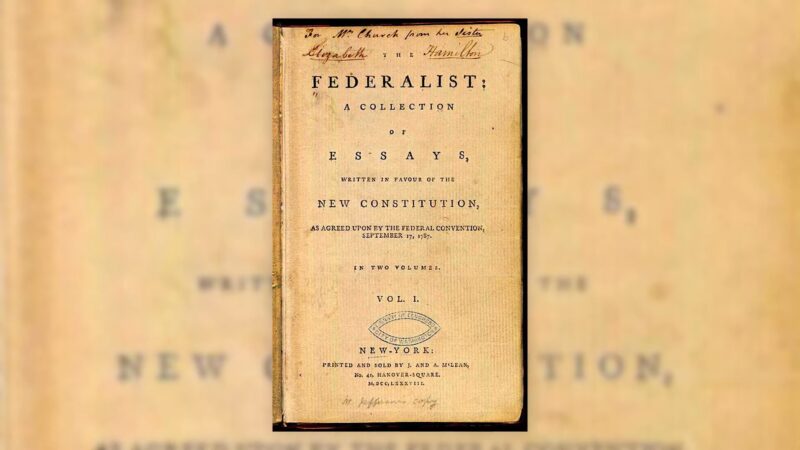

Federalist No. 10 was penned by James Madison in 1787 under the pseudonym Publius according to Study.com. Its publication on November 22, 1787, in The New York Packet, came at a crucial juncture in American history. This period, the post-Revolutionary War era, was marked by the weakness of the Articles of Confederation.

The ratification debates for the new Constitution sparked intellectual ferment. Differing visions for America’s path forward led to the establishment of factions. My composition here, Federalist No. 10, addressed concerns about the dangers of factionalism.

I argued for a large republic to mitigate the pernicious effects of factions. The diversity of a large republic, I believed, would prevent any single faction from dominating. In contrast, smaller republics were more likely to suffer from majority tyranny.

The historical landscape, marked by the Shays’ Rebellion of 1786-1787, exemplified the weaknesses of the Confederation. This insurrection highlighted the need for a strong federal government, capable of managing unrest and maintaining order.

My essay was a response to Anti-Federalist critiques and an effort to defend the proposed Constitution. By the time of this writing, states were deeply engaged in debates over the ratification of the Constitution, and the tension between Federalists and Anti-Federalists was at its height.

The Argument Against Direct Democracy

In Federalist No. 10, I highlight the issues surrounding factions and argue that direct democracy is inadequate to curb the dangers they pose.

Faction as a Dangerous Vice

Factions, I define, are groups of citizens united by some common passion or interest opposed to the rights of other citizens or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community. In my analysis, a dire consequence of such factions is that they often work against the public interest and infringe upon the rights of others. This, in turn, leads to instability, injustice, and confusion within the government.

Factions thrive in environments where there are fewer checks on their power according to National Constitution Center. With this in mind, I assert that pure democracies—systems in which all power rests directly with the people—are unable to effectively control factions without sacrificing the liberty which is essential to their existence.

Inability of Pure Democracies

In my observation, pure democracies have been historically unable to deal adequately with factionalism. Here, every citizen’s opinion has direct impact on the course of public policy. This system, while ideally promotes equality and participation, in practice allows factional interests too often to prevail over the broader public interest. Below is a comparison to illustrate the distinction:

| Pure Democracy | Republic |

|---|---|

| Decisions are made directly by citizens. | Decisions are made by representatives of the citizens. |

| Majority factions can easily dominate. | A greater number of factions balance each other out. |

| Less able to mitigate the effects of factions. | Better equipped to refine and enlarge public views. |

In a pure democracy, a majority can crush a minority purely on numerical strength, without an intermediate body to check the impulses of passion and to allow time for cooler deliberation. My argument intends to show that a great republic, constructed on the principles I advocate, is more likely to temper the dangers of faction and to protect the rights and interests of all citizens.

Features of a Large Republic

In Federalist No. 10, I identify that a large republic can better control factions and manage the diversity of interests compared to smaller republics. Here’s how:

Controlling Factions

In a large republic, the likelihood of a single faction gaining majority power is diminished due to the sheer number of voices and opinions. This complexity of representation makes it more challenging for any single group to dominate the political landscape. By extending the sphere of the republic, factions become less problematic as they are unable to unify the entire populace to oppress the rights of others or compromise the common good.

Diversity of Interests

A large republic comprises a wide array of interests and factions that check each other. This variety ensures that:

- No single interest can easily overpower others.

- Diverse interests encourage negotiation and compromise.

- The multitude of sects and interests form a mosaic of opinions that protects against the tyranny of the majority.

By promoting a pluralistic society, I argue that the inevitable differences among people are best managed within a large republic framework.

Republican Government as a Solution

In Federalist No. 10, I argue that a large republic is the best guard against the dangers of factionalism. In contrast to a pure democracy, where a majority’s interests may trample those of the minority, a republican form of government — where representatives are elected — has a distinct advantage. In this system, the public voice, expressed by their elected officials, acts to refine and enlarge the public views by passing them through a medium of a chosen body of citizens.

I assert that the representatives under a republic are:

- More likely to possess the wisdom necessary to discern the true interest of their country

- More likely to be patriotic and just, less likely to betray their trust

- Less likely to be driven by the short-term emotions of the people

The extent of the republic is also crucial. In an expansive republic:

- A greater variety of interests, parties, and sects will emerge, making it less probable that a majority will have a common motive to invade the rights of other citizens

- Even if a common motive arises, it will be more difficult for all the members to find each other and work together

Moreover, the republican principle suggests that a large republic will dilute the influence of factions over the elected representatives due to the higher number of voters and candidates, as opposed to smaller republics or pure democracies. This wider pool makes it more challenging for corrupt or unworthy candidates to gain enough support to be elected.

By expanding the sphere of the republic, factions become less threatening by being unable to gain nationwide dominance. This is why I firmly believe in the efficacy of a large republic to control factions and prevent them from violating individual rights or the public good.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the principal arguments presented in Federalist No. 10 regarding the control of factions?

I affirm that Madison argues the causes of factions cannot be removed without infringing on personal freedoms; thus, the effects of factions must be controlled. He posits a large republic is the optimal way to dilute the influence of any single faction.

In what ways did Federalist No. 10 influence the structure and provisions of the U.S. Constitution?

I observe that Federalist No. 10 heavily influenced the constitutional framework by advocating for a functional separation of powers and federalism, which are integral in mitigating the risks posed by factions and preserving the stability of government.

What mechanisms did James Madison propose for mitigating the negative effects of factions in Federalist No. 10?

I note Madison proposed an extended republic and a system of representation to mitigate factions. By having more elected representatives, the likelihood of any single group overpowering others’ interests would be substantially minimized.

Why is a large republic considered more effective in controlling factions, according to the arguments in Federalist No. 10?

I can confirm that in a large republic, the multiplicity of interests and opinions makes it less probable for a majority faction to form. This diversity acts as a barrier against the dominance of any one faction.

What is the significance of the majority faction concern raised in Federalist No. 10, and how does it relate to the political theory of the time?

I recognize the concern about majority factions as central to Madison’s argument, illustrating the potential for majorities to oppress minorities. This concept reflects Enlightenment thinking on the need to safeguard individual rights from the tyranny of the majority.

What notable expression is attributed to James Madison in Federalist No. 10, and what does it convey about his perspective on factionalism?

I point out the expression “the mischief of faction” is attributed to Madison, encapsulating his view that the infighting and divisiveness of factions are a threat to the effectiveness and stability of a democratic government.

Conclusion

In my analysis of Federalist No. 10, I’ve underscored the inevitability and danger of factions in a democratic society. James Madison argued that the causes of faction cannot be removed without destroying liberty. Instead, he advocated for a large republic where a diversity of factions would counteract each other’s influence.

My examination of this pivotal paper reaffirms its lasting relevance to the American political landscape, serving as a reminder of the ingenuity behind the U.S. constitutional design. The brilliance of Federalist No. 10 is in its acknowledgment of the perils of factionalism paired with a pragmatic approach to mitigating its effects.